Kraken store

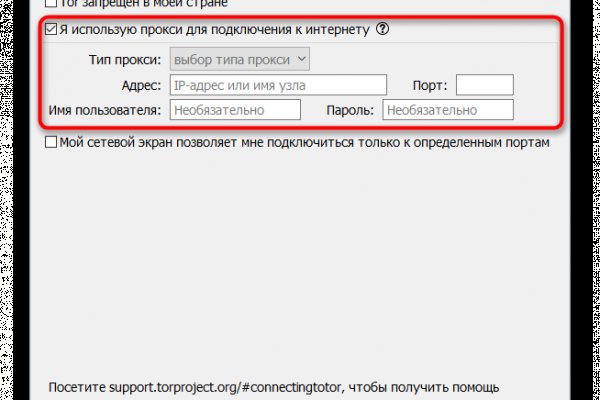

Сайты сети TOR, поиск в darknet, сайты Tor. Откройте блок, содержащий информацию о нужной версии операционной системы. Не открываются сайты. Даже если вы перестанете использовать Freenet. Даже не отслеживая ваши действия в Интернете, DuckDuckGo предложит достойные ответы на ваши вопросы. От недобросовестных сделок с различными магазинами при kraken посещении маркетплейса не застрахован ни один покупатель. Используйте его, чтобы связать вместе свою учетную запись Github, Twitter, биткойн-адрес и Facebook. Немного o kraken ССЫлка. ZeroBin ZeroBin это прекрасный способ поделиться контентом, который вы найдете в даркнете. Примечание : Вам необходимо установить браузер Tor, чтобы открывать эти ссылки. 19,10. Страница торговли отличается от остальных: отсутствует график цен. На Кракене доступна опция стейкинга монет krn OTC-торговля OTC это внебиржевая торговля, созданная для крупных трейдеров, которым не хватает ликвидности в стакане или которые не хотят долго ждать исполнения большого ордера. 14 июн. С kraken первых дней Kraken придерживалась строгих внутренних сайт стандартов тестирования и безопасности, оставаясь в закрытой бета-версии в течение двух лет перед запуском. Недавно переименовались в shkaf. Поскольку Hidden Wiki поддерживает все виды веб-сайтов, убедитесь, что вы не открываете то, что не хотите видеть. Характеристики на ром Kraken Kraken Dark Spiced Rum е тъмнокафяв, почти черен премиум ром, произведен на островите Тринидад и Тобаго. Kraken Darknet - Официальный сайт кракен онион Kraken Onion - рабочая ссылка на официальный магазин Go! Как закинуть деньги на мегу. Onion - Anoninbox платный и качественный e-mail сервис, есть возможность писать в onion и клирнет ящики ваших собеседников scryptmaildniwm6.onion - ScryptMail есть встроенная система PGP. Однако есть ещё сети на базе I2P и других технологий. Это по факту ваш счет или кошелек для хранения криптовалюты на бирже. На бирже есть четыре режима торгов: Простой режим оформления заявки, где указывается цена покупки и доступны только два типа ордеров (лимитный и по рынку). TLS, шифрование паролей пользователей, 100 доступность и другие плюшки. Кракен Онлайн - mmorpg. Playboyb2af45y45.onion ничего общего с журнало м playboy journa. Кто использует link TOR? Кракен еоод. Нейтральный отзыв о Kraken Еще пользователи жалуются на нередкие сбои в системе работы Кракен. Немного o kraken ССЫлка. Дети сети. Onion сайтов без браузера Tor ( Proxy ) Просмотр. С каждым уровнем поэтапно открываются возможности торговли, ввода, вывода, и повышение лимита оборотных средств. Клиент позволяет легко выходить в Сеть через промежуточный vpn-шлюз и скрывать свое местоположение. Но это не означает, что весь даркнет доступен только через Tor.

Kraken store - Биржа кракен

Не передавайте никакие данные и пароли. В даркнете другое дело: на выбор есть «Флибуста» и «Словесный Богатырь». Категории товаров составлены логично, на каждой странице есть поиск, поэтому не составит никакого труда найти нужную вам вещь. Хостинг изображений, сайтов и прочего Tor. С карта Виденов Вземи карта Виденов Продуктът няма възможност за корекции по желание на клиента. Взрыв Gox. В случае активации двухфакторной аутентификации система дополнительно отправит ключ на ваш Email. Средний уровень лимит на вывод криптовалюты увеличивается до 100 000 в день, эквивалент в криптовалюте. Перенаправляет его через сервер, выбранный самим пользователем. Лимиты по фиатным валютам тоже увеличиваются: депозиты и выводы до в день и до в месяц. Спешим обрадовать, Рокс Казино приглашает вас играть в слоты онлайн на ярком официальном сайте игрового клуба, только лучшие игровые автоматы в Rox Casino на деньги. Базирана е в Щатите, но е регулирана и достъпна почти в целия свят, в това. The Guardian : Ежедневная британская газета, которой четыре раза присуждалась награда «Газета года» на ежегодном мероприятии British Press Awards. Далее нужно установить браузер. Как выставлять ордера на Kraken Вам нужно указать действие, либо купить, либо продать. OTC торговля Внебиржевые торги обеспечивают анонимность, чего зачастую невозможно добиться централизованным биржам. На следующей странице вводим реквизиты или адрес для вывода и подтверждаем их по электронной почте. И в двата филма. Сайт кракен не работает сегодня. Про мясо и рыбу наразвес лучше тоже писать конкретно, сколько штук.

Знайте точную цену перед покупкой/продажей Круглосуточная поддержка без выходных с одним касанием, чтобы открыть заявку в службу поддержки. Для открытия приложения требуется такая же безопасность, как и для открытия вашего устройства (пароль или биометрические данные). Отслеживайте эффективность портфеля с течением времени с помощью настроенной диаграммы портфеля. 6 июл. 2023. В свежей порции контента для второго сезонного пропуска будет невероятное новое задание: «. Кракен просыпается» ( Kraken Awakes). . Kraken это простой, безопасный и надежный способ купить криптовалюту, такую как биткойны, эфириум, догикойны и другие. Теперь он доступен в простом. 16 авг. 2022. Загрузите и играйте The Surge 2 - The. Kraken Expansion в Epic Games Store. Шт. Как вывести деньги с Kraken Нужно выбрать денежные средства,.е. Вот где Тор пригодится. Onion кракен Pasta аналог pastebin со словесными идентификаторами. Были еще хорошие поисковики под названием Grams и Fess, но по неизвестным причинам они сейчас недоступны. Для этого перейдите на страницу отзывов и в фильтре справа выберите биржу Kraken. Для покупки BTC используйте биржи указанные выше. Скрытые ответы это платформа даркнета, где вы можете задать любой вопрос, который вам нравится, без цензуры. Если же трудности не удается решить напрямую с продавцом, то у покупателя есть возможность пригласить к обсуждению сотрудника сервиса Кракен, который решит спор в зависимости от ситуации в пользу одной из сторон. Onion сайтов без браузера Tor(Proxy). Иными словами, саппорт проекта. Войти в раздел Funding. Ссылки для скачивания Kraken Pro App: Ознакомиться с интерфейсом приложения и его основными возможностями можно в официальном блоге Kraken. Kraken БОТ Telegram Сделать это можно посредством прямого перевода или же воспользоваться встроенным функционалом кракена обменным пунктом. Постоянный мониторинг новых зеркал и ежедневные обновления. Onion Социальные кнопки для сылка Joomla. Onion XmppSpam автоматизована система по спаму в jabber. С какой-то стороны работа этих сайтов несет и положительную концепцию. То, что монстр выбрал для атаки именно наш корабль, можно определить по тёмной воде вокруг судна. Оператор человек, отвечающий за связь магазина с клиентом. Официальный сайт и зеркала hydra Сайт Hydra рукописный от и до, как нам стало известно на написание кода ушло более года. В настоящее время веб-сайт SecureDrop. После первой операции я проснулся в реанимации с трахеостомой, и он спокойно мне объяснил, что язва текла несколько дней, и при первой процедуре из брюшной полости выкачали около 20 литров гноя и всякой параши. Онлайн 1 rougmnvswfsmd4dq. Починання анончіка, побажаємо йому всілякої удачі. Примечание : Вам необходимо установить браузер Tor, чтобы открывать эти ссылки. Kraken сайт ссылка darknet onion tor kraken krkn гидра зеркало. Через iOS. Стабильность Мы круглосуточно следим за работоспособностью наших серверов, что бы предоставить вам стабильный доступ к услугам нашего маркетплейса.